Everyone is trying to read the tea leaves on whether or not the Supreme Court will uphold the Environmental Protection Agency’s Mercury and Air Toxics Standards rule, but like the horse that is already in the field, those emissions have already left the stack.

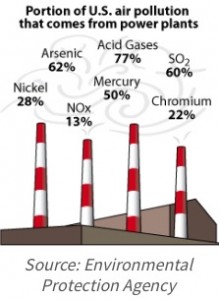

MATS, which is set to go into effect in mid-April, tightens restrictions on mercury and other pollutants, most of which come from coal-fired plants. That would be the death knell for coal plants, or so claim the coal heavy states and utilities challenging MATS that presented their oral arguments before the Supreme Court on March 25. To stretch the analogy, that bell has already tolled.

Utilities have had years to prepare for MATS, and most have either made the investment in the equipment to bring a plant into compliance or have shut, or announced plans to shut, coal plants that they deem would not be economic to retrofit.

From the coal perspective, the damage has already been done. “It is already too late for many coal plants to avoid compliance,” Julien Dumoulin-Smith, an analyst with UBS, says.

So why the all the attention on MATS?

The challengers argue that the EPA erred because it did not consider costs when it drew up the MATS rules. Those costs are not insignificant – the EPA estimates them at $9.6 billion – but they could pale in comparison to the costs of another rule that is now working its way through EPA’s regulatory process.

The so-called carbon rule would impose the first ever restrictions on greenhouse gas emissions for existing power plants. Some estimates put the compliance costs as high as $73 billion a year, which has sparked speculation that the proposed rule could be challenged because the EPA erred by not weighing the costs of its rule against the expected benefits.

If it were a horse race, the smart money would be on the EPA. The agency’s recent emission rules have withstood challenges in both appellate courts in before the Supreme Court. And the carbon rule itself is based on a finding that is the result of a Supreme Court challenge.

But utilities cannot afford to gamble on court outcomes. They have to prepare for what appears to be inevitable: There will be restrictions on carbon dioxide emissions.

In fact, MATS and the pending carbon rule only sharpen the focus on a longer standing trend. Coal is being driven out of the market by lower cost generation from plants fired by cheap natural gas – think hydraulic fracturing – and from renewables.

Power plants are long lived assets with high capital costs and long planning horizons that must pass muster at state regulatory agencies. Faced with even the prospect of CO2 emission restrictions, Dumoulin-Smith argues that many states will opt for the near term fix of adding solar or wind power to their mix rather than betting on a coal plant.

In this scenario, MATS doesn’t really matter, and the writing is on the wall. The reign of King Coal is over. He has been unseated by his cousin, carbon.